This story was first published here.

We meet in a café down the road from where the Berlin wall once stood. Olaf Schwarz is just as I remember him from our one encounter in 2014. Small, bespectacled and in his mid-sixties, he wears a silver chain around his neck and speaks so softly that I have to lean right into him to hear. He orders a beer.

I’d reached out to him because five years ago, on a bus ride to an event at which we were both volunteering, he’d mentioned that he used to work for East Germany’s state circus. He’d taken care of the elephants.

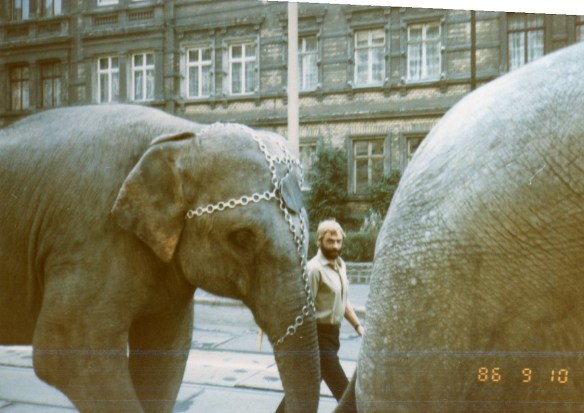

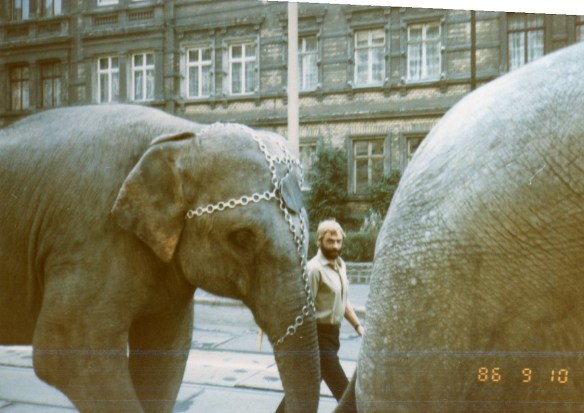

Olaf Schwarz taking care of elephants in the GDR in 1986 Photo: Olaf Schwarz

It’s the kind of fact that sticks and it came back to me as I was contemplating the economic impact of German reunification. I was on the search for somebody who could capture the experience of East Germans whose socialist world crumbled almost as abruptly as the Berlin wall did. Olaf Schwarz, I thought, could be my man.

On November 9th, 1989, when Germans rushed to tear down the wall that had shackled them for so long, two radically different ideologies came face-to-face for the first time in 28 years. On the western side was a nation with a thriving free-market economy that had experienced a ‘Wirtschaftswunder,’ or economic miracle. On the east was the Communist-run German Democratic Republic: a centrally-planned economy in tatters.

The GDR circus was one of many East German institutions that floundered and ultimately collapsed following reunification. Olaf Schwarz worked there between 1981 and 1987.

“It wasn’t hard to get a job in the GDR,” he says. “The circus was always looking for people.”

In many ways, it’s no surprise that he ended up there. In the years before, he’d spent most of his time hitchhiking, sleeping outdoors and avoiding the authorities. He first got a taste for it at the age of 12, when he and four friends set off on an ill-fated quest to hitchhike to the western city of Duisburg, because they’d seen a picture of it in their geography textbook. They stood on the side of the Autobahn and told the drivers who stopped for them that they were on their way to their grandmother’s funeral. Eventually, after a search warrant was put out, one of the drivers smelt a rat and the police caught up with them. Olaf Schwarz’s appetite for adventure was born.

Olaf Schwarz hitchhiking to Bulgaria in 1975

Unlike regular citizens, whose movements were heavily monitored and restricted, employees of the circus were allowed to travel freely. Their performances took them to West Germany, Austria and even Japan. The GDR authorities trusted them not to defect during their international performances. Were they right to?

“When I went to Austria in 1983, it did occur to me not to come back,” Schwarz says. But the conditions and hierarchies he’d observed at Western circuses put him off.

“The relationship between individuals of higher and lower rank was terrible,” he says, adding that the conditions at the GDR circus, where everyone and not just the boss had access to hot showers and a kitchen, “couldn’t have been better.”

Another distinguishing feature of the East German circus was that the children in the troupe got an official state education from accredited instructors who would accompany them on their travels. Childcare was provided too, and Olaf Schwarz fell in love with one of the Kindergarten teachers. In 1987, when she began to suffer health problems and was no longer able to travel, he quit the circus so they could stay together.

He got a job at an animal welfare organization, which was on a mission to control the wild cat population. “My job was to drive to wherever the traps had been set up and pick up the cats,” he says. A few months into his new post, one such journey brought him close to a pathologist’s clinic. It was to be a turning point in his life.

He got talking to a staff member, who invited him in to see a corpse. He gazed at it impassively. As a child he’d spent a lot of time observing operations at a slaughterhouse. Death didn’t faze him.

“The guy said that if this stuff didn’t bother me, I should go work for the Berlin municipal undertaking service. He said I’d earn double there.”

He took the man’s advice and traded cats for corpses. If the salary he’d been promised as an undertaker was good, the tips he got were even better. It was for this institution that he was working when the Berlin wall came down in 1989 and the socialist regime in which he’d come of age began its final demise.

“Sure, you could have seen it coming,” he says. “If you thought about it logically, it was clear that things couldn’t continue on as they’d been.”

In the beginning, nothing much was said and the staff kept on working as normal. Within weeks however, the old managers, all of whom had been members of the East German Communist Party, had been replaced. For Olaf Scholz though, an even bigger change was to come.

The following year, the East German currency, the Ostmark was replaced by the West German Deutsche Mark. “Overnight, the tips stopped,” he says. There is indignation in his voice. “We got nothing anymore.” I ask him why he thinks this was. “People were too stingy to give away their Western money,” he says simply. Perhaps, I think, they realized its worth.

The GDR undertaking service did not survive long after reunification. There was briefly talk of it remaining a government entity, but the well-established private funeral parlors in west Berlin spoke out in opposition. Once again, it was time for Olaf Schwarz to look for a new job.

Never one to turn down a challenge, he became a security guard for a private US security company in west Berlin. He even got a firearms license as part of his training. His job included patrolling the villas by the Wannsee lake, which to this day are home to some of the city’s wealthiest residents. To a person who had spent almost three decades living in a system that forbade the accumulation, let alone the flaunting of wealth, it must have come as quite a shock.

“It was interesting,” he says. “Some of the villas had swimming pools in their basements. And places to dock their boats.”

He worked in the security business for several years, before once again getting a job at a funeral parlor. He was there all the way up to 2007, when the business folded.

It was then that his first and only prolonged period of unemployment began. It was to last for a decade, until he reached retirement age.

He filled his time taking free courses for people out of work. He learnt how to operate a camera and it was in this capacity that we met in 2014, when we spent a day working together to produce a report about an event at a seniors’ club in Berlin. Today, he continues to shoot videos, which he uploads to his YouTube channel.

One of the greatest pleasures and challenges of storytelling is when the tale you thought you were going to tell morphs into something else. Before our conversation, I thought that Olaf Schwarz might represent a kind of common East German experience. Perhaps, I thought, as he reflected on his time at the circus, he would display a certain kind of Nostalgie, a yearning for the certainties, if not the repression of the GDR regime. Alternatively, I considered, maybe he typified the East German who was quick to embrace the freedoms that capitalism offered. An entrepreneur of sorts who was able to grasp hold of new opportunities.

Both narratives are far too limiting. Like the millions of Germans whose sensibilities were shaped by the cold war, his response to the political and economic events of his time was entirely unique. If I did have to identify a single thread that has run through his life and got him to where he is today, it would be a healthy disregard for authority.

“To be honest, whether it was then, or now, I don’t trust any government,” he says. “I just do my thing.”