I’m used to having a couple of holes in my clothes. It comes with the territory of being one of those people who occasionally leaves the house with a dress on inside-out and whose bag contains a decade-worth of receipts and a half-melted Mars bar.

And it’s fine, really. I’ve got this far. The sub-group of perfectly put together individuals is already large enough.

But there came a time, a few weeks ago, when the number of holes in my clothes was becoming disproportionate.

“What’s going on?” I asked LSH, waving my green woollen cardigan, brown knitted dress and – tragically – a brand new sweater from Uniqlo before his sleepy yet not indifferent eyes.

His fate was similar.

“I wore this coat tending goats in Norway,” he said sadly. “I’ll never be able to replace it.”

We filled black bin bags to the brim and – not knowing where else to go with them; it did not seem right to transfer a potential infestation to the Red Cross clothing bank – popped them into the Restmüll container.

I ransacked Rosmann’s anti-moth section, buying bundles of lavender, rings of cedarwood – and only in case of emergency – sticky paper.

We emptied our wardrobes and used our weak-powered, spluttering OK brand vacuum cleaner to remove every last speck of dust.

“It’s the honesty I appreciate,” LSH says of the Hoover. “It’s just OK. It doesn’t pretend to be anything more.”

I found four lifeless caterpillars, which I removed using a plastic shot glass and a business card from someone at the World Bank.

Our life returned to something resembling normal. With the range of our outfits diminished, what remained in our wardrobes had more room to breathe.

We became accustomed to the smell of lavender and cedarwood in our bedroom.

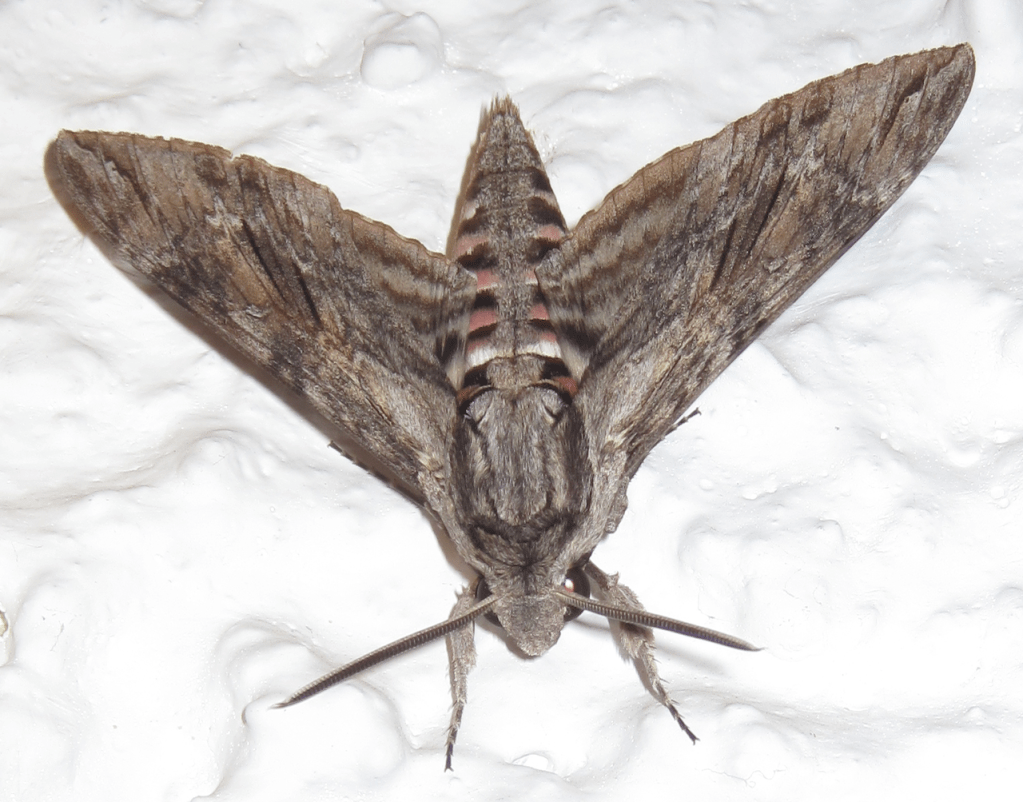

Still, often, more often than we liked, we spotted moths. They loitered on the bathroom wall, and on the kitchen ceiling. Their shadows haunted us.

Research had taught us that they weren’t the enemy. It was the larvae – invisible to the naked eye – that had the insatiable appetite. They only ate organic – wool and cotton were their favorite.

But the presence of these matriarchal moths was a cause of concern. They flew about with authority, mocking us as we chased them with the plastic shot glasses; their confidence was of the ripe and reproductive kind. Thankfully, an outrageously opportunistic real estate agent had recently written asking if we would like to sell our apartment. He had enclosed a high-quality business card in the envelope. It was ideal for catching moths. We became better hunters.

We removed them – humanely of course – one by one.

“Just tip them over the balcony,” I told LSH. “They’ll be alright, they can fly.”

I bought more bundles of lavender. The waft of cedarwood became more intense.

Time passed. The pandemic raged on. We spent our evenings watching the French version of possibly the worst television program ever made, The Circle.

“We need to talk,” LSH said one day.

We had already agreed that the bureaucracy of a divorce in this country would be too much to handle. Besides, we had been getting on just fine. And he was the one who had suggested we watch Le Cercle.

“It’s about the vacuum cleaner.”

He took my hand compassionately and like a woman condemned, I followed him to the living room.

He picked up the small, red OK hoover. “I’ve found the source.”

Inside the dust bucket, beyond the fluff from our socks, the crumbs of our dinners, the remnants of our dead skin, the Hoover brimmed with life. A mass of white eggs, a smattering of tiny caterpillars, an occasional fully formed moth.

I squeezed his hand tightly and for several days, we did nothing. The word moth did not even pass our lips. We were, I can see now, in shock. We were not OK.

During our ordeal, in a period otherwise marked by inertia, we got a new Hoover. LSH spent ages researching and in the end we opted for a not-particularly-cheap Philips model. Its power is inordinate. Vacuuming is a joy we argue over and emptying the dust bucket a near-religious ritual. Sometimes, especially when you are in your thirties, it’s OK not to be OK.

Yesterday was a national holiday in Germany. “Christi Himmelfaht” marks the ascension of Christ into heaven, 40 days after his surprise resurrection.

Inspired by the painful events that led to this glorious flight, I decided to sacrifice myself to the cause of dealing with the moth nest in our vacuum cleaner.

As liberal snowflake vegetarians, we do not enjoy killing though we are also complete hypocrites because we do eat pesto.

LSH thought Restmüll was the answer.

“I can’t,” I said. “That’s an awful death.” I had just been reading about the ecological advantages of moths in The Guardian.

I googled: How to remove a moth’s nest humanely.

Nothing.

I put the vacuum cleaner in a black bin bag and put on a pair of disposable gloves we’d bought at the beginning of the pandemic.

I walked self-consciously to the park. It was raining, which I had hoped would make things easier. But the joggers were out in force. Germans are hardy people.

I made my way through a clearing in the bushes and took a deep breath. I opened the bag. For the first time, I examined the life inside carefully. I hoped that no one was watching me. I did not know how to explain.

I clicked open the dust bucket and tipped the contents onto a bed of moss.

On the way home, I walked to the bins in the communal courtyard and discarded of the rest of the Hoover in Restmüll. A better person would have brought it to the recycling center but the sticker on the bin said that the rubbish inside would be burnt to power homes across the city. There is only so much virtuousness possible in one day.

I returned to the apartment, shaken but satisfied.

“They are risen,” I told LSH.